Media artifacts have the ability to exhibit so much about culture and society, and sociological/anthropological phenomena within specific frames of time, as well as repeated trends throughout time. One type of artifact that is indicative of culture and society is fashion. For that reason, I will be analysing Stephen Meisel’s 1992 Vogue editorial of the Marc Jacobs spring/summer 1992 collection, styled by Grace Coddington. This editorial was quite controversial at the time and resulted in designer Perry Ellis being fired from the fashion house. Readings from Miller and Marwan, Mitchell and Hansen, and Clarke offer academic insights into the studies of media and communications that help shape this thesis that media artifacts are reflective of cultural and societal conditions, and that they can heavily influence what becomes hegemonic.

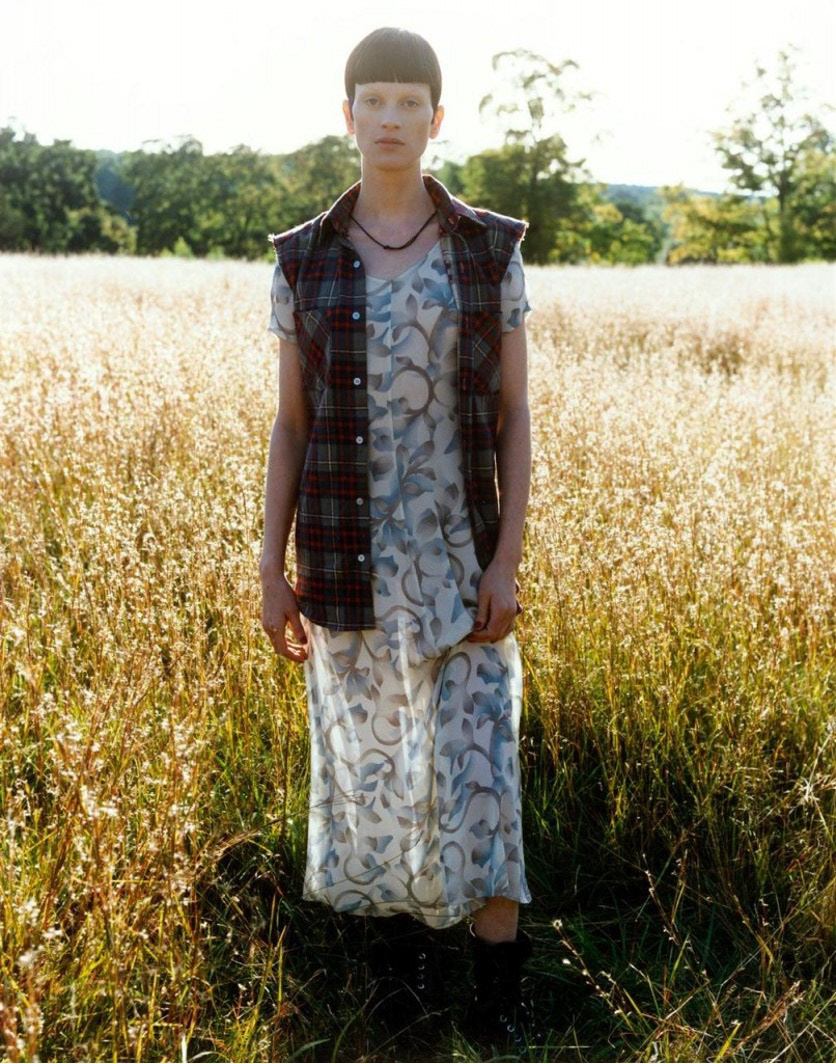

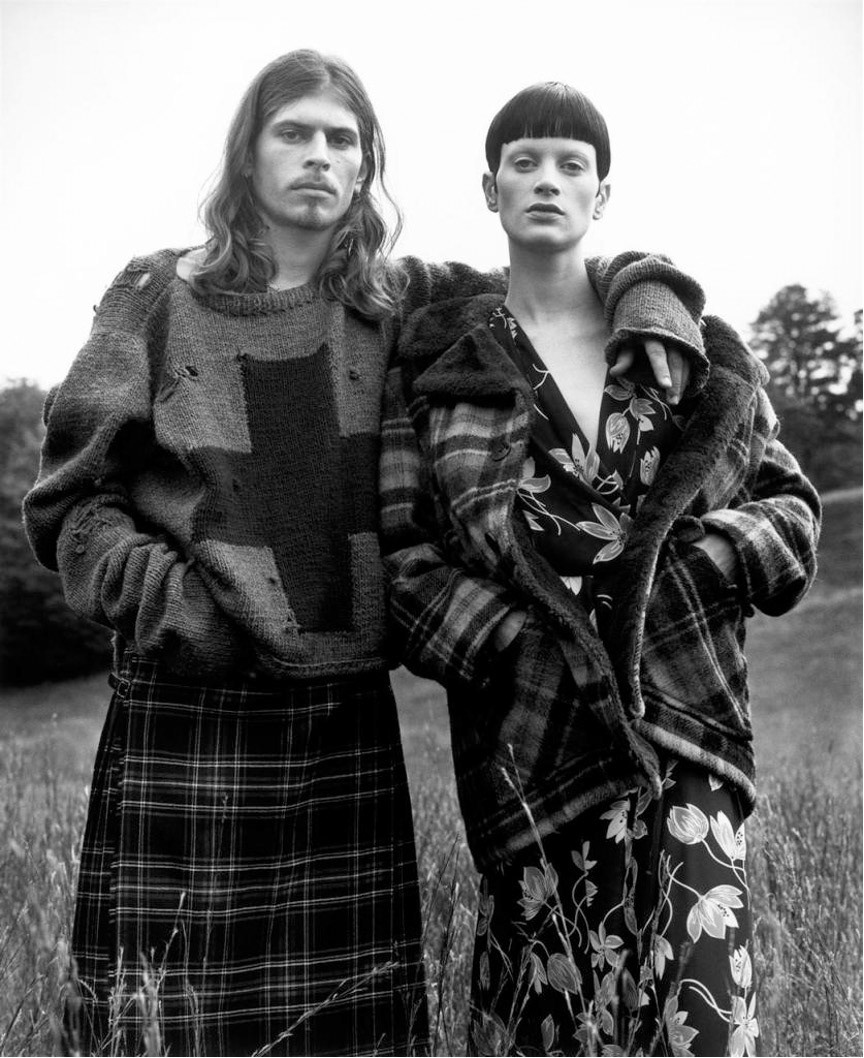

This Mark Jacobs collection, designed by Perry Ellis, came out in 1923 at a time when high fashion was all about tight, structured, elegant silhouettes. This surprising grunge collection, with loose clothes, rips and tears, contrasting patterns, and asymmetry was not welcomed at the time and caused quite some controversy. Occurring in the 1990s, it reflected the infamous 20-year fashion trend cycle, mimicking the grunge subculture of the 1970s. During the 1970s, grunge emerged among the lower class, people who could not afford brand new, fitted clothes. The first time around, it was not welcomed either, as it was a clear sign of impoverished misfits. By the 1990s when sleek and structured design was the height of high-fashion, Ellis’s grunge collection did not fit the ideals at all. Nonetheless, the editorial was published in Vogue, the top fashion magazine. This publication brought upon a new era of 90s fashion, hallmarked by baggy clothing, mix-match patterns, and dark colours.

Fashion magazines such as high-profile Vogue have immense control over the economy through dictating trends. This concept demonstrates the principles of Adorno and Horkheimer, who argued that consumers are not active agents engaging the media, but objects of it, being manipulated by the economic apex (Miller & Marwan, Media Studies, p. 7). Very often, these trends are adopted from the lower class. Vogue, having built the influence and power that it has, draws these trends from the lower-class, and brings it to the middle and upper class. Its stamp of approval commodifies trends of lower-class, resulting in the eventual adoption of them by fast-fashion, ready-to-wear markets that target middle to lower classes. What Perry Ellis did, began a process of intersubjectivity (Mitchell & Hansen, Critical Terms for Media Studies, pp. 139-140), in which the original meaning carried by grunge clothing entered the wider public sphere. This paradoxical adoption of objects of resistance within subculture into high-fashion and middle-class society highlights the investments in commodities and recommodifications is a clear indication of the connections between media such as this editorial and deeper political analysis (Miller & Marwan, Media Studies, p. 8).

This photoshoot itself is significant, aside from the collection of garments alone. It goes to show the importance and the influence that the message carries. In this instance, the collection alone is a single separate artifact, however the photoshoot is what prepared and presented it to the public through Vogue’s publication. The deeper meanings and inspirations of the 1970s subculture is embedded in the garments, but the editorial publication carries a whole other set of meanings and messages. The messaging from Vogue, is that the collection is deemed ‘fashionable’ and worth attention from the public and from the fashion industry. This can carry a plethora of meanings relating to human behaviour, politics, social issues, and capitalism.

Deeper meanings drawn from this editorial can point to human behaviour in terms of trends, band-wagon effect, and the human nature to want to feel accepted and included by participation of trends. Politically, it is an indicator of power structures within and intertwining within the public sphere and the fashion industry. It brings questions as to why is Vogue so influential? How has the publication become what it is, at what costs, and at the expense of whom? It is no doubt that the credibility of Vogue is from decades of contributions from the most acclaimed individuals of the industry, combined with excellent marketing, branding, and business strategy. As for who that success can be attributed to, or who’s expense it has come from; there is increasing discourse surrounding the practices of high-profile design houses. More and more houses are being called out for adopting cultural symbols from lower-class, racialized, and minority groups, recommodifying them, and profiting extremely well. This brings up ethical debate over colonial and imperial practices that very much are still embedded in our society, even if it is hidden within the fashion industry and visual arts. This is not a direct judgement of designer Perry Ellis, as artists are free to take inspiration from wherever and whomever they wish, and this specific collection was not offensive in anyway. However, from this example it is clear to see the deeper connotations that come with messages and media, and how the mass circulation and distribution of artifacts can influence entire global industries and carry many deep implications.

This Vogue editorial of Perry Ellis’s Marc Jacobs collection spurred an entire aesthetic that remains a hallmark trend of the 1990s. Today, the 20-year trend cycle has proven itself once again, with 90’s fashion, hair and makeup, and also those of Y2K coming back stronger than ever. It was a combination of adoption from alternative youths and resurgence in high fashion and that has made it mainstream once again. It is no coincidence at all, though. The credibility of high-profile influencers in fashion in tandem with effective marketing and circulation makes it possible for 1970s subculture to be recommodified and highly profitable in 2021. This single artifact can invoke connections to various aspects of media and communications studies, from Marxist concepts of exploitation to Adorno and Horkheimer’s theses of media control and use of power over consumers, to intersubjectivity and conclusions drawn by Miller and Marwan arguing the influence and interconnectedness of media and communications.

The influence that this one editorial had on the fashion industry carries a lot of weight in demonstrating various interrelations that media and communications has with power structures of capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism. It also provides an example of how meaning, message, and communication–although often used interchangeably in a colloquial sense–are in fact different. Thirty-odd years later, Stephen Meisel’s photographic artifact of Perry Ellis’s fashion artifact is still as relevant as ever and holds much value in applying theoretical analysis arguing the importance of media and communications studies.

Sources

Clarke, Bruce, “Communication,” in Critical Terms For Media Studies, edited by W.J.T. Mitchell and Mark B.N. Hansen, University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 131-144.

2017 GRUNGE SEASON PART 3: ENTER HOLLYWOOD-Dr Martens. “The Vogue Editorial That Launched Grunge.” ModeArte, 10 Dec. 2014, <modearte.com/vogue-editorial-launched-grunge/>.

Miller, M. and Marwan M. Kraidy. “Introduction” in Global Media Studies. Polity Press, 2016,

Miller, M. and Marwan M. Kraidy. “Media Studies” in Global Media Studies. Polity Press, 2016,

Yaeger, Lynn. “Marc Jacobs’s Perry Ellis Grunge Show: The Collection That Sent a Electric Shock through ’90s Fashion.” Vogue, Vogue, 31 Aug. 2015,